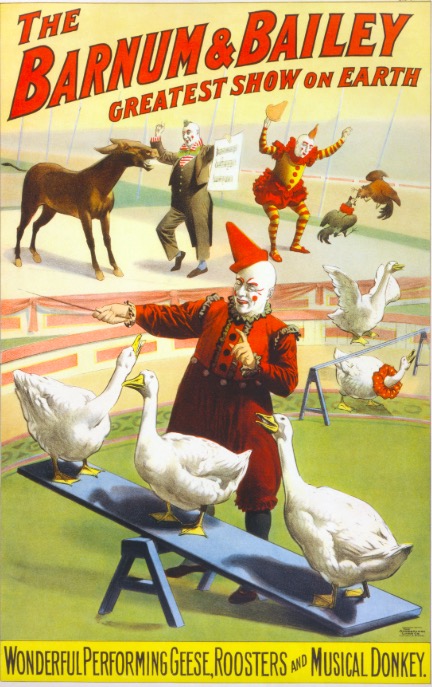

"That is no reason at all," said I, "and therefore I'll believe in the mermaid, and hire it." "Because I don't believe in mermaids," replied the naturalist. "Then why do you suppose it is manufactured?" I inquired. He replied that he could not conceive how it was manufactured for he never knew a monkey with such peculiar teeth, arms, hands, etc., nor had he knowledge of a fish with such peculiar fins. Not trusting my own acuteness on such matters, I requested my naturalist's opinion of the genuineness of the animal. Kimball, who brought it to New-York for my inspection. He died possessing no other property, and his only son and heir, who placed a low estimate on his father's purchase, sold it to Mr.

Still believing that his curiosity was a genuine animal and therefore highly valuable, he preserved it with great care, not stinting himself in the expense of keeping it insured, though re-engaged as ship's captain under his former employers to reimburse the sum taken from their funds to pay for the mermaid.

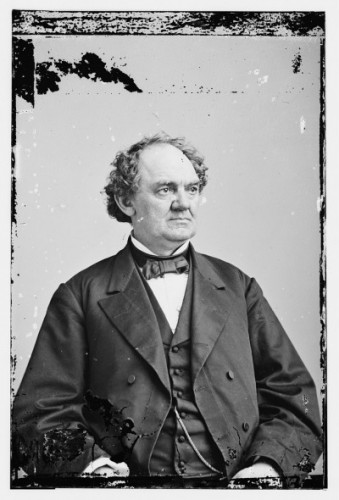

He did not realize his expectations, and returned to Boston. Not doubting that it would prove as surprising to others as it had been to himself, and hoping to make a rare speculation of it as an extraordinary curiosity, he appropriated $6000 of the ship's money to the purchase of it, left the ship in charge of the mate, and went to London. He stated that he had bought it of a sailor whose father, while in Calcutta in 1817 as captain of a Boston ship, had purchased it, believing it to be a preserved specimen of a veritable mermaid, obtained, as he was assured, from Japanese sailors. Early in the summer of 1842, Moses Kimball, Esq., the popular proprietor of the Boston Museum, came to New-York and exhibited to me what purported to be a mermaid.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)